🎬 Sh*t I Should’ve Done #3: The 47-Min Short That Should’ve Been 15-min

Feb 09, 2026

Recently I was telling a story about happy accidents on set, and I brought up a short film I directed called Minor Blues. It was my second film, and I was (and still am, I guess) learning how to tell a story.

I wrote the script with my writing partner at the time — and she’s a really great writer. On the page, everything worked. The problem is… it was an ambitious short. I don’t remember how long the screenplay was, but the finished film was 47 minutes long. Yeah. It was a short. 😅

And the thing is, it had all the ingredients: great script, solid cast, strong visuals. But it also suffered from all the underfunded, early-career, “I don’t know what I don’t know yet” mistakes that a lot of short films suffer from. So, since this is a blog episode of Sh*t I Should’ve Done, let’s dig in.

First: yes, I wrote it with a partner. By the time I shot it, we were no longer partners. I was — and can still be — a bit single-minded. At the time, my focus was becoming a filmmaker, and I had very little patience for anyone who wasn’t taking it as seriously as I thought they should. I’ve since calmed down, but whew… that attitude rubbed people the wrong way. And I should’ve handled the situation better — but that’s a story for another blog.

Before we parted ways, we were rehearsing the film with a group of actors we cast together. Then the film fell apart. After we split, I was able to get the project back on track, but with a few different actors. They were great, but again… the project was ambitious.

We had roughly a 40-page script.

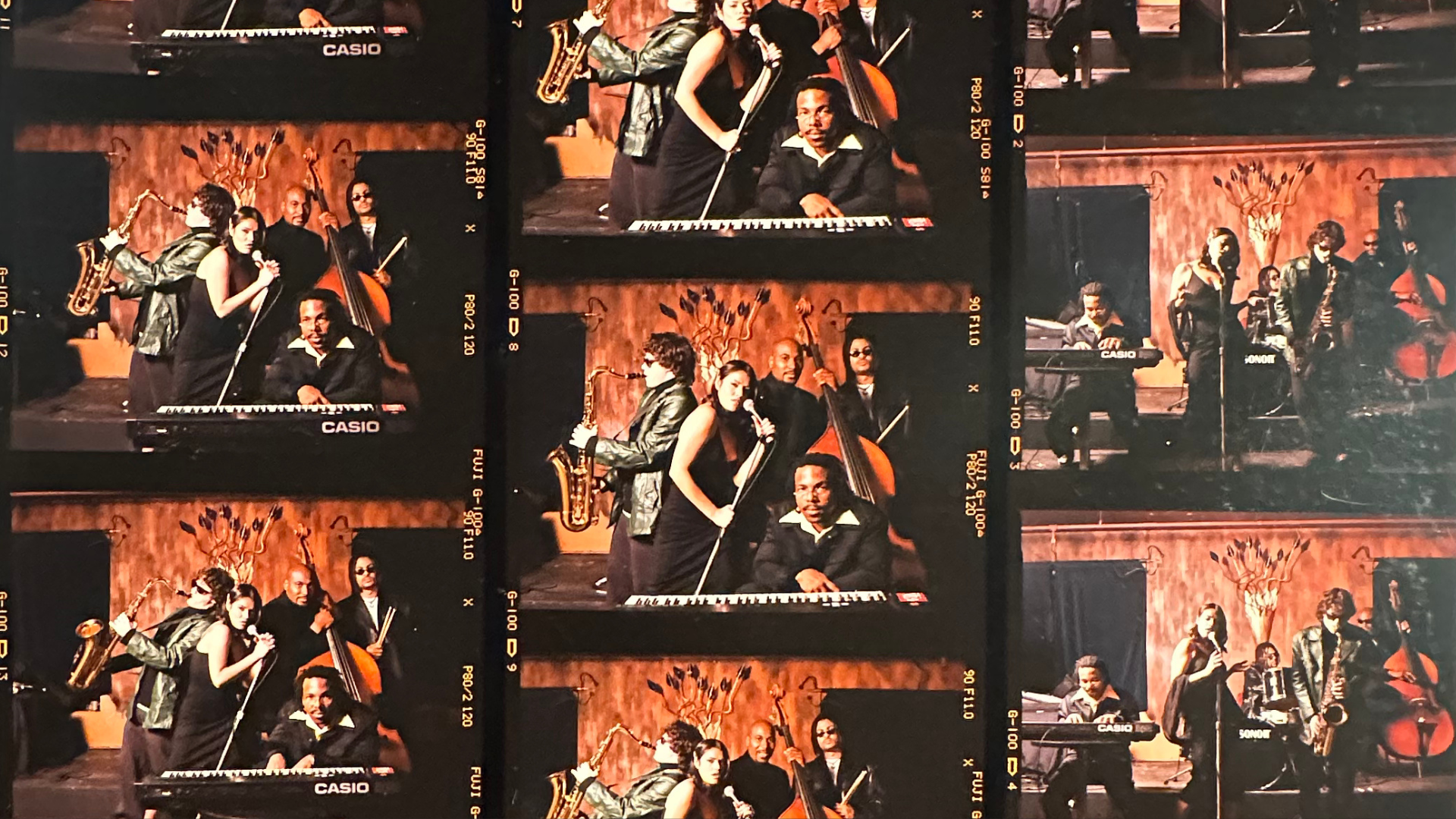

I had five leads who had to play instruments and we needed the instruments.

I had a deaf character who needed to learn sign language.

I had about 10 locations spread over four different counties.

I had an actor standing on the ledge of a building acting drunk — in the dark — with no safety precautions. (Yes, I’m judging younger me. Hard.)

One actor dropped out mid-filming, so I had to replace him and rewrite scenes as we were filming. And mind you — we were shooting out of order, so he popped back in from time to time like, “Surprise! Remember me?” 😩

And then… I used unlicensed music on the soundtrack. So when it was time to submit to festivals, I had to re-record it. But by then I was in love with the unlicensed tracks, and the film was never the same. Even my father said, “I liked the other music better.” He was my biggest fan — RIP Dad.

One of my actors lived in New York by the time we started filming, so we had to fly him out on Spirit Airlines. The flight got canceled and rescheduled for the next morning, and he had to sleep in the airport. The truck I used to pick him up and cart the crew around had a suspension issue and rocked side to side. I didn’t know that until I got on the freeway to drive from the airport two hours to the first location. We all held our breath and said silent prayers. Just chaos.

Now… a lot of our locations were free. And while this whole thing was a case study in being too ambitious, it was also a case study in what you can get when you simply ask.

We (me & my producing partner Alisa Lomax) got a crew to work on a short film for free or dirt cheap — and many of them I still work with today. This was also AJ Crimson’s first film (RIP). We shot one location overnight on Easter — a bar in Greektown. The bar owner didn’t charge us a thing. He literally came in and slept in the kitchen while we filmed.

We even had an overnight location where we booked the cheapest motel we could find. The mold on the wall was so bad it looked like wallpaper — I kid you not. I showered partially clothed. It was funky.

We lost a location the day we were supposed to shoot, so we walked around the corner to a Greek restaurant and asked if we could film there. They said yes. We had to keep repeating ourselves because we weren’t sure they understood what we meant. We even laid dolly track in there. Like… who does that? We did. 😂

For all that went wrong, a lot went right.

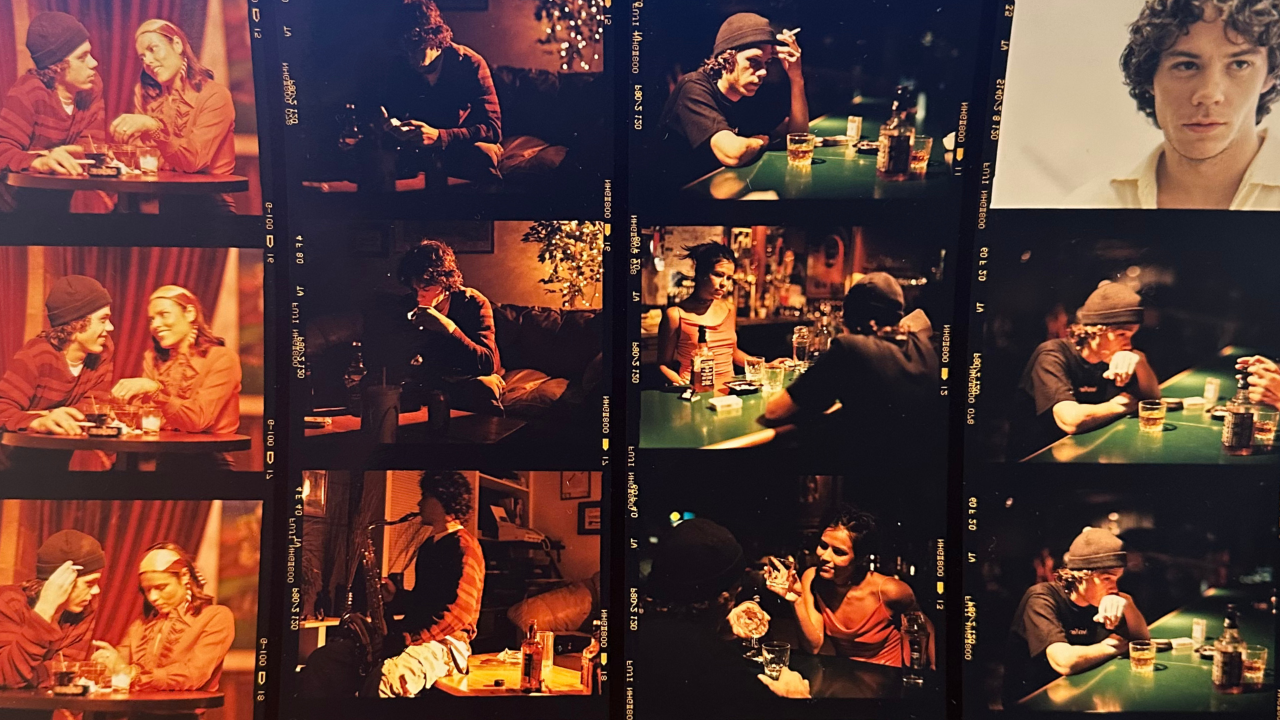

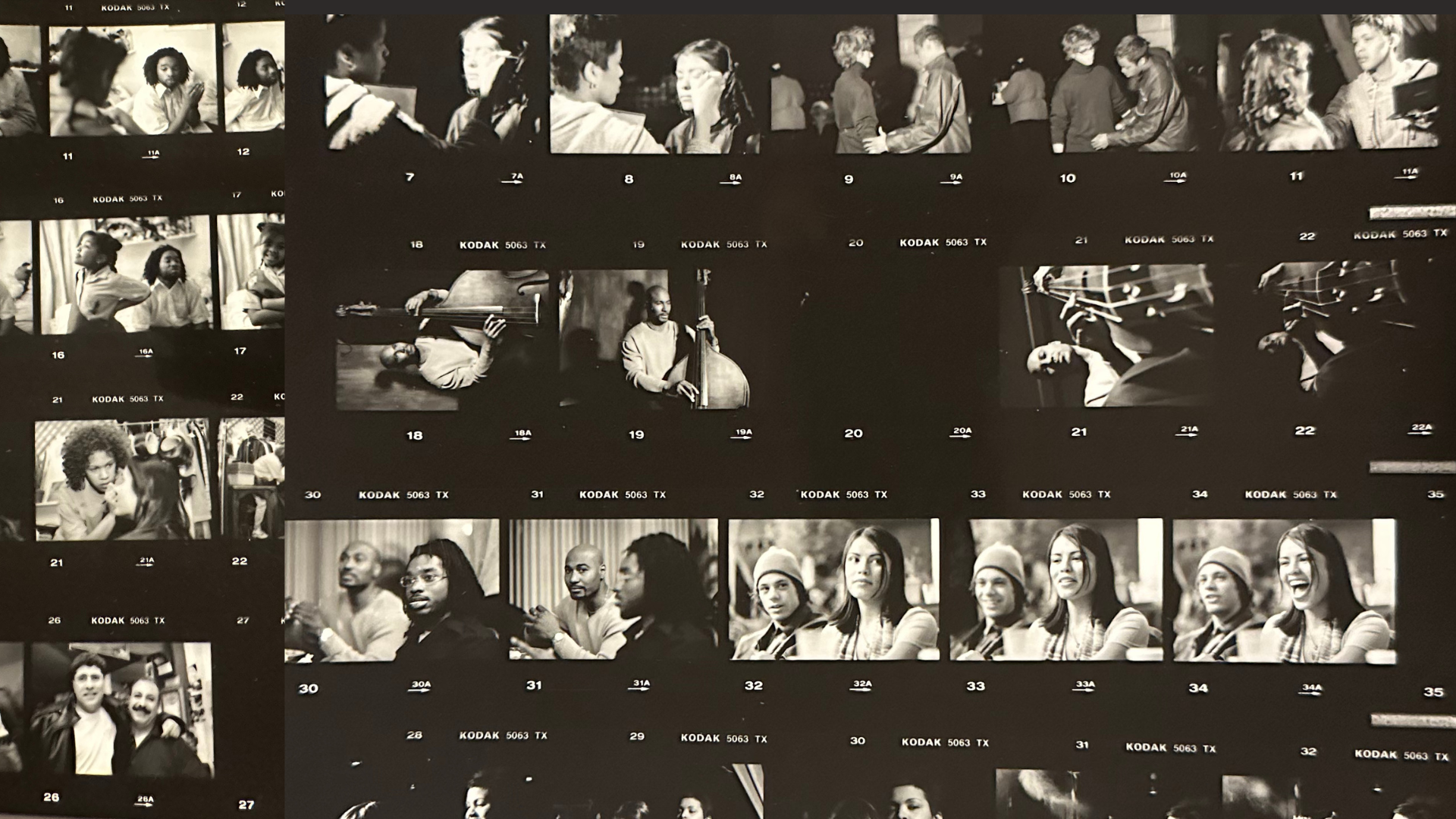

And visually? The film was gorgeous. We shot on 16mm color film, and every set was practical and full of production value. My DP, Dominic Cochran, was amazing – the entire crew for that matter.

And in spite of all the issues, I rolled with it. I was resilient. I loved it. We were making a movie. The crew and I were in it together.

The editing process was also amazing. I worked out a deal with a sound designer and we did Foley — real Foley work in a booth — my first and only time doing that. And what he did with sound design taught me early on why it’s so important.

But what really did me in was the finished film.

Because I was so in love with the footage, I thought I had to use everything. I had never heard the phrase “kill your darlings,” and I was afraid — very, very afraid — to cut anything. So, I carted around my 47-minute short like it was The Godfather. Proud as I could be.

My father loved it (again: number one fan). My family loved it. We screened at a few local festivals. Then it got honored at the Meet Martell at the Movies Festival — branded content before branded content was a thing. I don’t even remember how it came together, but I wholly underestimated it.

They held a screening at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit and hosted a really nice reception — serving Martell, of course. It was a great night. And here’s where I messed up: my friends and family had already seen the film a couple times, so I didn’t invite anyone. Also… I didn’t know it was going to be that nice.

Then I got on stage for a Q&A and completely flaked out. Nobody had questions — probably because I was acting nervously shy and I wasn’t prepared to talk about the film. I should’ve been confident and proud that day. I can still be shy, but now I’m much more comfortable speaking in front of crowds about my work because I love what I do so much.

Looking back, I feel bad about that event. It would’ve been nice to share that night with the cast and crew — and of course my dad. But I truly thought everyone had seen it enough and wouldn’t want to be bothered.

Now here comes the biggest mistake of all.

I didn’t apply for a $30k grant specifically for filmmakers of color. To enter, you had to submit a 15-minute short film. Word was spreading about it, and I didn’t apply.

You want to know why?

Because there was no way I could cut my masterpiece 47-minute short down to 15 minutes. Everything was important — or so I thought. How could I even make that happen?

And listen — there’s no guarantee I would’ve won. But I had as good a chance as anyone.

The next year — after I left the cable company and started freelancing full-time — I worked with a filmmaker (who I’m still friends with today) who had won the Showtime competition. She was living in California but wanted to come home to make her film. And that’s when it really hit me.

By then I had some distance from minor blues and could admit the truth: the 47-minute version had issues. But a tight 15-minute version? That would’ve been gold.

Actually… I’m impressed with myself (and the team) for pulling any of it off.

But what I should’ve done was:

- Revise the script to fit my budget — or raise more money.

Trying to bend reality to match ambition is a losing game. Either scale the script or scale the resources. - Having locations in three different cities, hours apart from each other, was ridiculous.

Travel eats time, energy, and money. Consolidate. Cluster. Be practical. - Have a real safety plan — period.

An actor standing on a ledge in the dark with no precautions? Absolutely not. Even or especially on a micro-budget, safety has to be a line you don’t cross. Harnesses, spotters, permits if needed — or rewrite the scene. - Lock the music strategy and don’t edit to a temp track.

Using unlicensed music and then trying to replace it later almost broke my heart. Either secure the rights early, commission original music, or never get emotionally attached to anything you don’t legally own. Don’t edit to temp tracks. No, no, no. - Build a schedule around reality, not hope.

Multiple counties, multiple locations, complicated scenes — I scheduled like everything would go perfectly. Nothing ever goes perfectly. Always build in travel time, delays, and breathing room. - Make a shorter cut for opportunities.

I could’ve created a tight 15-minute version for grants and competitions and still kept my longer “director’s cut.” Instead, I treated my 47-minute short like it was sacred text. It wasn’t. Flexibility opens doors. I’m sure I missed out on opportunities.

But honestly? Every chaotic step taught me how to make the next film better — and that’s the real win.

P.S. I talk about all this and more in my Self Paced Movie Making Masterclass is available. If you’re ready to produce your own film — with a little less guessing and a lot more guidance — learn at your own pace. Your one masterclass away from making that film.

🎬 The Filmmaker Starter Pack

A FREE cinematic toolkit to kickstart your first feature-including Nicole Sylvester's funding guide, microbudget video replay, templates, and live consultation access.

When you sign up for a resource, I'll also send you email updates on my latest blog posts, VIP content and the occasional product recommendation. Of course, I will always respect your privacy and data.